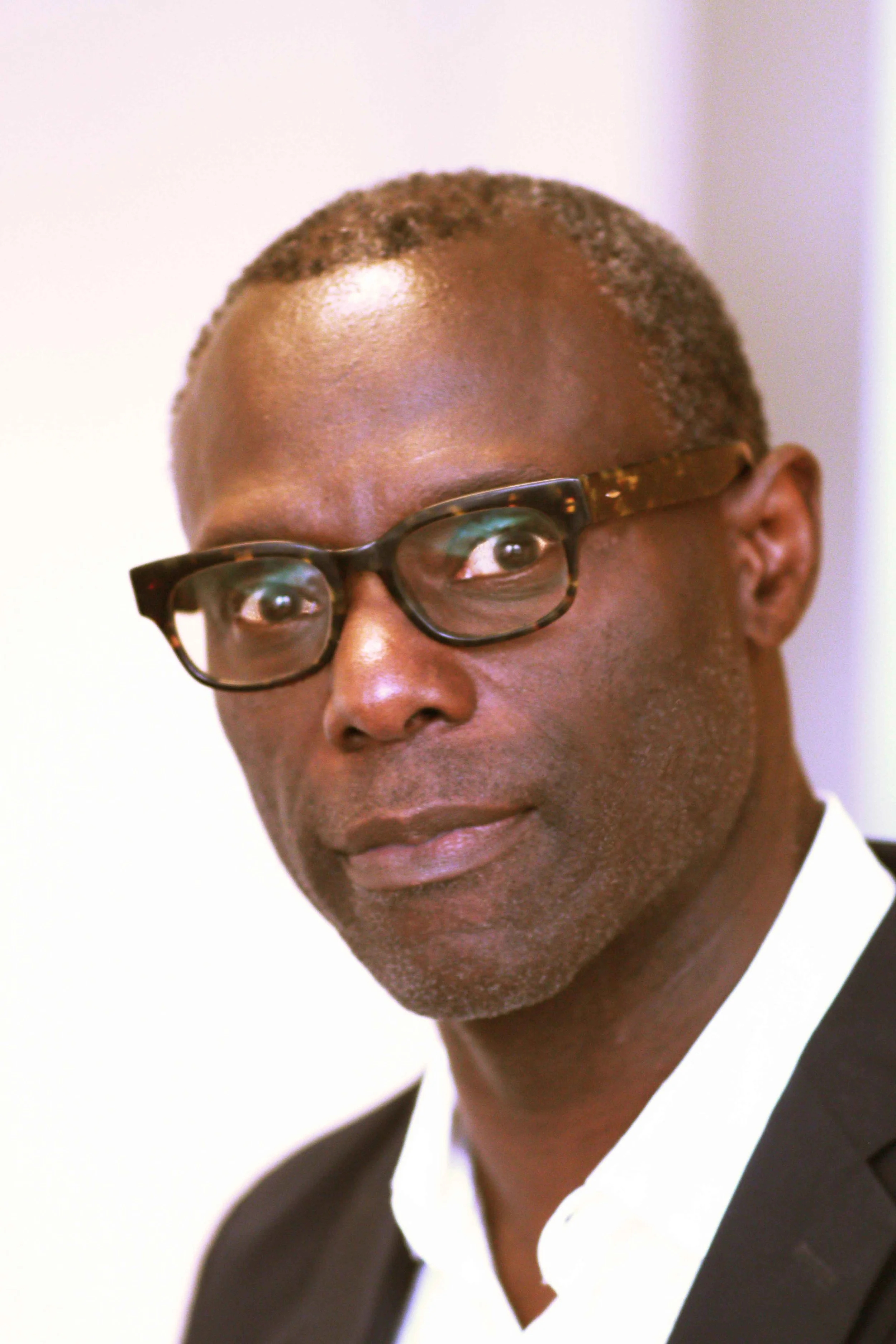

In Depth: Mykaell Riley (Steel Pulse)

Celebrating the 40th anniversary of their infamous album, Handsworth Revolution and the 50th birthday of Reggae, Steel Pulse’s Mykaell Riley caught up with Jessica Daly to discuss fighting the Metropolitan Police on racism, fighting policy on the basis of right to earn from your art and challenging those that questioned the legitimacy of Grime. ‘The revolution must be reenergised.’

“The beginning of Steel Pulse was a journey out of school. Trying to fulfil our parents’ ambition was where we were at but in reality, trying to get a job and to get through college all presented huge challenges for us. At first as a band, we were reflecting our daily experiences through song and about our lives as they unfolded. We were in a politically charged period where that was the done thing, the politics was right in your face and if that wasn’t enough, we had the police in our face every day.

It’s often over looked that back in the 70s, Jamaicans that were born there and moved here were considered proper Jamaican and that we were some distant relationship and not really Jamaican at all. We were born in the UK but our parents weren’t. They believed that we were far more British than they could ever be. The reality is that we had the same challenges as them, we had no chance of getting a job, into a club or even getting a gig so it wasn’t easy. Just the idea of being a bloody musician was thought as absolute nonsense by everyone. Especially being a black musician in what was a very pop and rock orientated climate, getting a reggae gig was seen as a joke, even by Jamaicans.

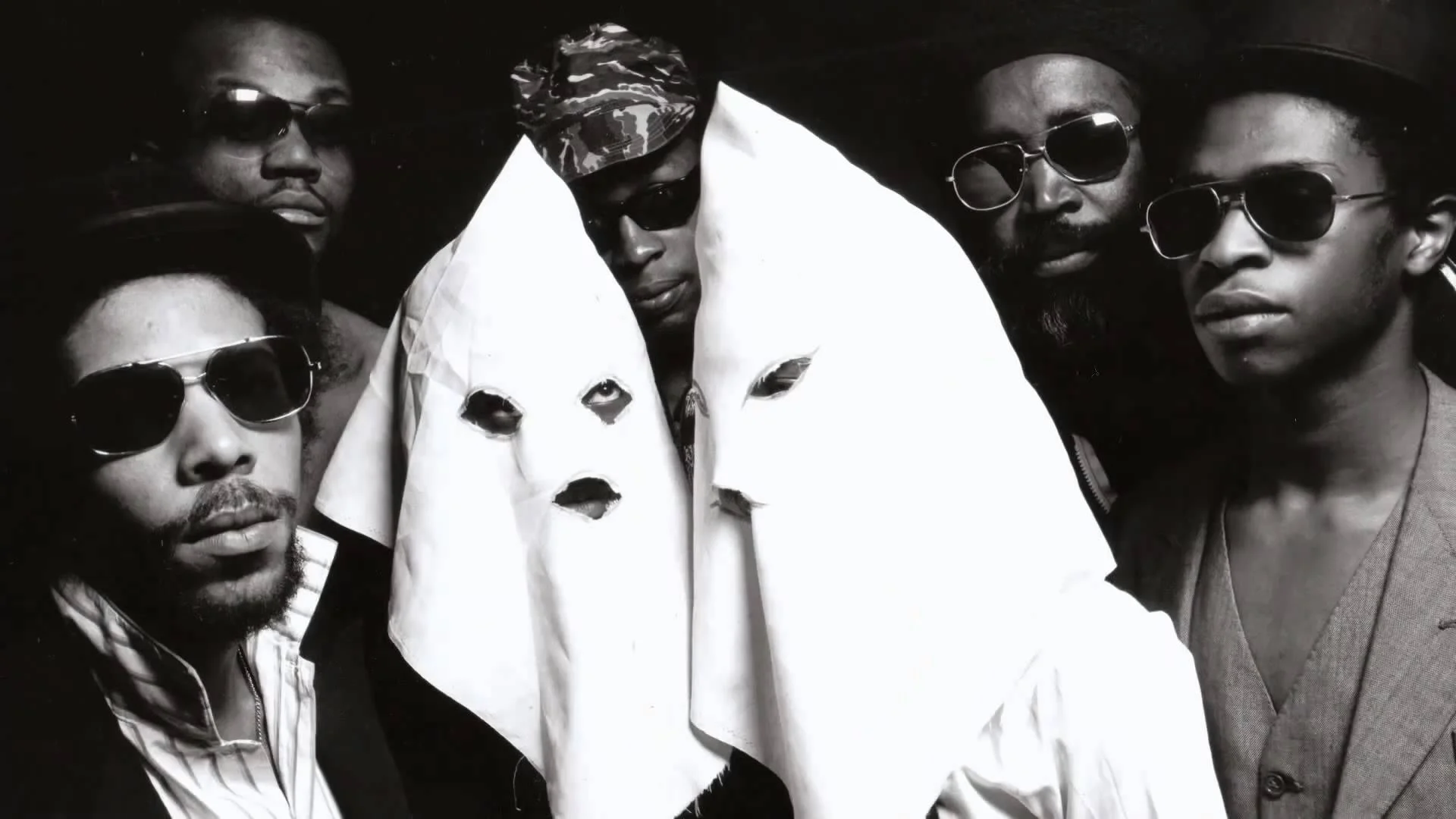

The track Ku Klux Klan which was on the album Handsworth Revolution has many roots to the song. We were reading about the States which highlighted that the last lynching was in 67 / 68. That brought everything from our lives into perspective, such as being beaten up by the police and in some cases, Handsworth people have even been killed by the police. So, we were looking at a way of connecting our experience with African American struggles.

I made the Klan hoods for the performance of the song; they were fuelled by the desire to make an immediate connection with the narrative of the lyrics, we wanted a knee jerk reaction from our audiences. We wanted the attention of those who jump on stage, throw beer at you and start a ruck for fun. At the same time though we were trying to be serious and communicate the message. You want to be understood so we did this through the performance medium.

There was resistance to the song initially and the BBC had it banned. We started to pick up air time and they were concerned like the ‘form 696’ by the Met Police, they thought our songs would incite civil unrest. The fact it was banned, really speaks on how politicised the radio is and how policed Radio 1 really is. Little did they know, most people didn’t understand what the fuck we were saying anyway! It is an interesting song because people sort of woke up half way through, once getting into the beat and explosion of reggae, they then realised we were actually very serious in what we were saying. It is a powerful song that even resonated long after we got off stage because we’d often be back in a situation where, we were even fighting members of our audience.

It’s not often told that Steel Pulse did more work with Punks on the road than any other reggae band at that time, and they became our audience. They really were, hard core punks. The punks were saying, look we’re not going to learn instruments, we’re not going to sing in tune and we’re not even going to dress like you. We don’t have a job so we don’t give a shit! The black community had a very similar mantra, we couldn’t get the jobs because we’re black, that of course had a serious impact. As young people we got together which meant that gulf between punk and reggae wasn’t there. I asked a member of the band the ‘Ruts’ once said to me, what do you think we listen to when we’re not making that fucking noise? Reggae mate! So the connection there was really quite fantastic.

I went back to Handsworth, where we’re from for the Punch Musics , Bass2018 event in Birmingham a few weeks back and it was absolutely fantastic just to have the whole subject matter remembered. The event was celebrating 50 years of reggae and 40 years of our album. They painted our album cover ‘Handsworth revolution’ on a wall in Handsworth Park. It felt like no time had passed, simultaneously celebrating it’s 40 decades but then reflecting on how little has changed.

In fact, it’s got worst and revolution needs to be almost reenergised because people have got complacent on the basis of all the work that was done, not just by Steel Pulse but also Birmingham and the Midlands, we challenged what was happening in the UK.

Going back to Birmingham really energised me but it was also really fucking depressing mate. I realised by going back, standing there while people were talking about the album, showed just how slowly change comes about. It means there’s a greater burden on each of us to try do something. Handsworth revolution at one point brought the community together. We were talking really proudly, you heard it being played from cars and the community owned it. For the time in many ways, we were made visible to rest of the UK. During that period we also joined Bob Marley on his first European tour. In terms of ambition, we fulfilled this for many in Handsworth and showed the people that anything is possible.

In Birmingham a few weeks ago, I felt like we’ve dropped the ball as a community though and somehow slipped backwards, we are no longer visible to rest of the nation in that way. Talking about it all at Bass2018 in context of the mural was really important for driving that force. It felt like Birmingham was doing something again, it didn’t matter that it is a Steel Pulse mural. Birmingham was saying that this is an achievement and it should be recognised by the industry as a success, and recognised by the community as a success. We’re going to paint it as a big fuck off mural in Handsworth park to make that statement. We’ve faced many challenges and even by the record label on the title with them asking who gives a shit about Handsworth. WE DO - We fought to say, that’s what we’re talking about in the album, our lives and our challenges.

At Bass2018 everyone gathered around the mural, press was there, the Mayor and Mayoress came to support the local community and the mural. It was a very wide demographic of people, experiences and there was some really interesting questions being fired at the panel during the Q&A too. On the panel was myself, Basil from the band and Danny Burke a photographer. We met two twins from the audience, who were easily in their 60s with an original copy of the album and were keen to get a complete set of signatures, 40 years later! People came and travelled far just for the event so that was great to see.

The work I do now, really is the same sort of work as when I was in Steel Pulse. I’ve set up the British Black Music Research Unit, although, I don’t see myself as an academic but more as an interloper – here to disrupt! The work I do in simple terms is recognising Black British music and ensuring it’s recognised in academia because at the moment it isn’t. It’s like it never happened! Culturally, contribution is absent. If you’re talking about popular music and a whole period of music that is absent then something’s wrong.

In the mid 70s we used to refer and look at Academia as a part of Babylon, controlled by the state, for the state and it certainly wasn’t somewhere we wanted to be. Jump forward 3 or 4 decades, I realised that unless your contribution to culture and history is written down, in books and being studied - You don’t bloody exist! That became a challenge in the same way as making the Klan hat, making that statement visually, even before you understand what’s being said.

The Research centre causes people to turn around and question, what is it and what does it stand for? One of the studies I conducted, Grime Report, goes back 15 years. It’s looking at how the law changes around music and is applied quite specifically to black music and black musicians. In the case of Grime, the report maps what happened since 2002 and around So Solid, this is when they introduced the policy which kicked off in London, Policy 696. It’s basically a risk assessment form that focused on a particular act or artist that potentially possesses more of a risk to the public and venue than anyone else. Over the years the Police in London specifically targeted black music whether it be Bashment, Dancehall, Grime etc. They fiercely restricted performances and stopped artists playing who were not negative or who had a violent audience at all. The challenge was, how can we get rid of that policy and how do we approach that.

We had to first challenge the music industry on the idea that grime is not a legitimate genre! This is what was being said all the way up to the middle of 2016 by the OCC (Official chart company) and by the BPI (British Phonographic Industry). I was asking them for music data on Grime to show for the first time just how successful Black British Music is. No one was saying no but no one would give it to me either. They told me Grime isn’t really a legitimate genre, which what they meant was, they were not earning from Grime and it doesn’t go through their systems.

So then we had to see whether we could collect this data and challenge legitimacy. Then expose the system in that this is, a real genre recognised in the UK and that it’s been ostracised. The Grime Report is the first that uses big data, this data comes from Ticketmaster. They use ticket sales to collect data and sell onto Live Nation, one of the biggest promoters in the UK. To actually get Live Nation to share the data with me, took 3 years in total. The report shows the innovation, ingenuity and creativity among the Black British community and an alternative means of earning. It actually embarrasses the industry, as it shows them playing catch up, which is laughable.

Between the middle of 2016 and the start of 2017 the industry goes from ignoring Grime, but awarding artists who are influenced by grime. To then overcompensating by nominating grime artists like it was going out of fashion. Which in itself damaged grime a little. If you over expose a genre it burns out. We didn’t change the law but it was the straw that broke the camel’s back as they took the report to city hall. We went from fighting the Metropolitan police against racism to fighting on the basis of right to earn from your art.

Some of my other research involves our Bass Culture project. It took me 8 years to get the funding and deliver the project. That’s again resistance and involved fighting resistance from the power that be. Now we have the biggest exhibition on the subject happening in London at the moment. Black British Music still doesn’t really exist as an academic HE or higher education topic but If all goes to plan then in 2020 we will have BBM taught as University course internationally, we already have 9 UK partners and some in America.

Part of establishing this exhibit and project, is challenging how we think. We have pop music, classical, jazz, folk etc now we need to change the narrative of BBM. Hopefully that trickles down to places like America where they ask stupid questions like ‘oh, so you have black folk in the UK?’“